As we seek to reach ever-higher and more sophisticated levels of genetic technology, we must proceed responsibly — and with a certain humility.

That fourth-century scholar from the northern coast of Africa underwent a profound religious conversion after many years of living in immorality and self-indulgence. Long feeling called to faith and a moral life, but unable to make the leap, he is said to have uttered a wry (and insincere) prayer: “God, grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.”

Augustine finally became a Christian in his early thirties, abandoning his youthful fascination with the Manichaean concept of a dualistic struggle between cosmic forces of good and evil that influenced so many schools of philosophy throughout the classical world.

Under the prayerful encouragement of his mother, Monica, he came to realize that all creation is a product of the divine will. Therefore, life is sacred and should not be abused or misspent.

Perhaps his former dissipation gave him special insights into physical life. Augustine eventually understood that salvation is a gift of God acting within our mortal being — materiality infused by grace, body and spirit together.

This truth was demonstrated by the Incarnation, when God became one of us. And its reality has become ever more apparent as human understanding of physical life has increased through the progress of medical science.

We’ve reached the point now where doctors can make fundamental changes in our basic physical elements — our DNA — through genetic engineering. Gene-altering techniques, many of which are still largely experimental, have already shown tremendous promise in correcting genetic defects and treating disease.

RELATED: IVF companies slammed for screening out babies with undesired genetics: ‘This is evil’

I recently read about a seven-month-old boy suffering with a liver condition for which there is no conventional medical cure. Gene manipulation has arrested the deterioration he had been experiencing, and doctors now project that he will be able to live a long, normal life.

Impressed as we may be by such accomplishments, we must remember their source. It is God who has given man the intellectual ability, the creative intuition, and the analytical perseverance to delve deeply into the components of life and improve the health and wellbeing of all.

If there was ever a need for proof of divine inspiration, then surely such therapeutic marvels as this provide it. They also underscore the profound moral obligation that accompanies every significant advance in scientific and medical knowledge.

As we seek to reach ever-higher and more sophisticated levels of genetic technology, we must proceed responsibly — and with a certain humility. The great Catholic geneticist, Jérôme Lejeune, once observed, “The scientist is one who admits without shame that what he knows is microscopic compared to all that he does not know....”

This vital truth must always be borne in mind. Because techniques that promise great rewards can hold the prospect of great tragedy. Medical history provides many illustrations.

I’m old enough to remember the great Thalidomide scandal of the 1950s. This Swiss-developed drug has proven useful in treatments of cancer, various skin diseases, and even HIV. But it was first introduced as a therapy for pregnant women experiencing severe nausea and stomach upset.

The wholly unanticipated side effect was extreme deformities in their children, many of whom were born without arms or legs.

Mary Shelly’s famous gothic novel Frankenstein has long served as a literary warning about scientific hubris. Her central character, Victor Frankenstein, searched for the key to life, and wound up creating a monster.

More recently, Michael Crichton’s sci-fi novel (and movie) Jurassic Park told the story of prehistoric animals brought back to life through cloning, and running amuck in the island resort created to display them.

In an unsettling echo of the Jurassic Park idea, scientists from a company called Colossal Biosciences have announced the “de-extinction” of the dire wolf, a canine breed that hasn’t been seen on Earth for more than 12,000 years.

Perhaps the most damaging recent example of unrestrained scientific innovation gone awry is COVID-19. How the pandemic was loosed on the world five years ago remains a subject of great dispute. What is clear now, however, is that this novel coronavirus was the direct result of what’s called “gain-of-function” research likely related to anti-biological warfare.

Genetics is to the health sciences what Artificial Intelligence is to digital technology. These two exciting fields have been advancing along parallel lines but are now beginning to converge.

A.I. is being applied to biological research and data analysis, even as genetic understanding influences the development of super-high-speed computer circuitry and robotics. Organic/digital hybrids are a realistic prospect of the not-too-distant future.

This is another area in which we need to hear from our new Augustinian Pope. I suggested recently that Leo XIV needs to develop an encyclical or major statement on the moral implications of Artificial Intelligence . One about genetic engineering should be next on his agenda.

Clearly, the Pope understands the moral magnitude of this issue. In a note marking the start of the 3rd International Bioethics Conference, he encouraged an “interdisciplinary dialogue grounded in the dignity of the human person,” that can “foster approaches to science that are increasingly authentically human and respectful of the integrity of the person.”

As St. Augustine discovered, life and the ability to enhance it are gifts of God’s grace. Science and medicine are man’s response. We must take care that in our attempts at betterment, we don’t create the conditions for harm or even destruction.

The future of humanity is too important.

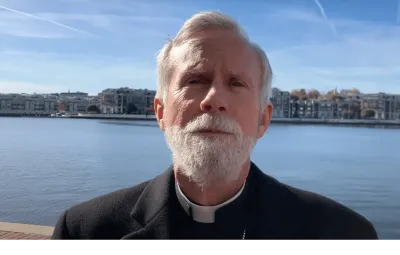

Rev. Michael P. Orsi is senior advisor to Action for Life Florida and host of “A Conversation with Father Orsi,” a weekly television series that delves into current events with a focus on sanctity of life issues. His writings appear in numerous publications and online journals. His TV show episodes can be viewed online.